The 1968 Democratic National Convention, held at Chicago’s International Auditorium, was eclipsed by the chaos happening directly outside: the televised spectacle of brutal, ongoing street battles between thousands of Vietnam war protesters, the Chicago police, and the Illinois National Guard.

Robert Forster was there. Best known for his Oscar nominated role in Quentin Tarantino’s JACKIE BROWN (1997), the actor covered the tumultuous ‘68 convention as a local TV news cameraman… only he wasn’t a real newsman, and his “Channel 9” didn’t actually exist.

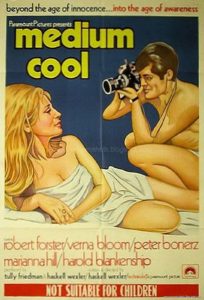

Forster was working undercover as he starred in his first independent feature film:

Nearly fifty years later, MEDIUM COOL (1969) endures as a landmark of freeform, neo-documentary style filmmaking, and a late sixties cultural and political touchstone.

I met Robert Forster at Silver Spoon in West Hollywood.

JON: You’ve been coming to The Spoon for a while now, haven’t you?

ROBERT: Since Schwab’s Drug Store closed in 1983. Which happened very suddenly: this whisper passed through the store—shocked faces everywhere—and they closed that day. Schwab’s had opened in 1941. It was always full of writers and directors, a lot of actors; horse players, hookers, and hangers-on. They would take messages for you there; it was just a great place. And when it closed, the regulars all scattered to the four winds. So some actors, myself included, went searching for another place to be in the morning—you have to be somewhere, right? We tried a couple places, then came here. Since 1984, I guess, I’ve been here on a near-daily basis. I used to sit inside with that bunch of actors, then my career got so lousy for a while, I started taking college classes, and moved out here to the patio so I could read and study. Then everything changed for me again after Jackie Brown; people wanted me again. So now I study my scripts and make calls out here. This has been my spot for about seventeen years. It’s nice to have a spot.

JON: You’ve described Medium Cool as a very seat-of-your-pants, heavily improvised production, with a constantly evolving storyline. What was the initial script like? The feeling of the material you first committed to?

ROBERT: I think the original title was The Concrete… I dunno, Concrete something-or-other. It was this story about a young boy who’d come to Chicago from West Virginia with his mother. There was no father. And this nice news cameraman gets involved with him, and his mother. It was a love story. The politics were in there a little, but nothing like what the movie turned out to be. You know, a movie with a very strong political point of view, made by a man with very strong political views, Haskell Wexler. He’s best known as a cinematographer, which he’s won multiple Oscars for, but he’s only directed a couple things. This is the important one.

JON: Was it the first lead role you were offered?

ROBERT: It was, in fact. I had supporting roles in my first two pictures, John Huston’s Reflections in a Golden Eye (1968), and a Western, The Stalking Moon (1969), with Gregory Peck. But this one required me to do all sorts of things I hadn’t a clue about, one of which was: even if there’s nothing written on the page, you’ve got to come up with something for the guy to say! It was a pretty big shock to me: I was still trying to figure out what a movie actor needed to know; you know, how you do it, and do it well.

On Medium Cool we had all kinds of opportunities to improvise; some of them even led to new scenes. There was a dinner scene, and I told the boy that I boxed at the CYO, and maybe I would take him some time. It was just a passing remark; that boy had never acted before, so I was saying things as a way to engage him. A few days later, Haskell comes in and says he wants us to do a scene at a fight gym. We actually shot that scene at the gym in Chicago where Muhammad Ali trained. So we’re there, shooting our improvisation, and he walks in! Came up the stairs, and everybody just stopped whatever they were doing. Everybody wanted to talk to him. We were kidding around some, and I said it’d be nice if he came up again and walked through our shot. He laughed and said, “No, no. If I walk through that shot, you’ll have to give me first billing!”

JON: You look pretty good in that scene. Did you box?

ROBERT: Nah. I just used to hit the bag a little at the YMCA in Rochester, New York.

JON: Feature film cinematographers generally don’t get too involved in working with actors. How did Haskell Wexler treat his first film cast?

ROBERT: Very generously. I mean, he really had his hands full there. It was a small movie, and he was trying to get it shot. Once in a while there was a second camera working, but he shot most of it himself. I think he expected the actor to read the script, understand it, and bring something to it. He expected them to know what they were doing. And I had to rise to that professional level.

JON: One of my favorite scenes is when you and Peter Bonerz go to meet all those black guys… and they start hassling you!

ROBERT: Fully improvised.

JON: I thought so. It’s just a… y’know, everybody in it is so good!

ROBERT: How about Felton Perry? When he does that talk right to the camera at the end?

JON: It’s like what Spike Lee did twenty years later: having his actors break the fourth wall like that. I just love the visible discomfort of you guys. I can’t imagine people had seen that in a movie before: black people just dressing down and taunting white people like that. Medium Cool has a lot of that: a lot of anger and disbelief is expressed, all related to the social turmoil of the times. Yet your character is disconnected from it all. He doesn’t relate very well to the events he’s witnessing. Did that at all reflect the way you were at that age?

ROBERT: I surely had no political point of view when I started that movie. I tried to get into that character through his professional point of view: a cynical news cameraman who’s just there to get the story. Doesn’t matter if someone’s bleeding; that’s somebody else’s job. He’ll call an ambulance, but only after he gets the pictures he needs. That’s the job, and that’s who he is: the unaffected one. I think that’s what Haskell intended him to be.

And again, the picture was completely restructured after it was shot. We shot an enormous amount of scenes, and the movie only uses maybe a quarter of them. We’d started out making a movie about a boy from West Virginia, and it became this political movie about the Democratic National Convention.

MEDIUM COOL trailer:

ROBERT: It was actually supposed to open with us interviewing Bobby Kennedy. We were supposed to see him in Washington on a Thursday, I think, and that Tuesday, my mother-in-law—we were living with my in-laws then—my mother-in-law yelled up to us in the bedroom, “They’ve shot Bobby Kennedy!” Within hours I got a call saying our trip was off, but then Haskell called soon after, and said we’d still go. So we were in Washington; four, five days after the assassination, and we actually filmed the preparations for his funeral. Those scenes of Bonerz and I going around the city in a taxi, watching the TV crews setting up, those towers they’re building; that’s what all that was for. That happened just as we started the movie, and the convention and the rioting happened right at the end. So those two events did a lot to shape the picture.

JON: So you started in June. There were already a lot of people very worried about what would happen in August. A lot of the radical groups were publicly announcing their intentions to disrupt the proceedings. Was Wexler already aware, already imagining that the convention could be a key backdrop to the story?

ROBERT: Oh, by all means. It was in the script, right at the end: one of those quarter page descriptions that doesn’t tell you a lot, but you know it’s going to take eight days to shoot it.

JON: So the assumption that there was going to be civil unrest was part of his planning?

ROBERT: Absolutely. All those guys—The Yippies, and so on—they said what they were going to do. And they did it.

JON: Were you getting nervous at this point?

ROBERT: Nahh! You know, we went up to Minnesota; we shot that stuff of the National Guard practicing riot control. But it was a yuk; you see those guys are kidding around—

JON: Yeah, but everything they do comes back for real around the convention.

ROBERT: Yeah. Remember at the end, you hear someone in the crowd yelling to the TV crew, “Don’t leave us! The whole world is watching!” That might have been the moment that phrase was coined. I’m not sure of that, but it might be.

JON: The protests and street battles began on Friday, August 24th; the convention itself opened on Sunday, and ended on Wednesday. How many of those days did you spend filming around there?

ROBERT: All of them. We shot in the convention itself for a very short time. I can’t remember the details, but I think we could only get two credentials to get on the floor. I found out much later—I think from Haskell—that it was Warren Beatty who got them for us. He was thick with the Democratic Party then, and he arranged for those two passes.

JON: What kind of credentials were they? Press?

ROBERT: Yeah.

JON: So you were actually in there as a real reporter?

ROBERT: Yeah.

JON: That’s what it looks like, but I wondered.

ROBERT: We could only use them for an hour or something. It was a very brief thing; just Haskell and I on the floor. I was shooting the convention, and he was shooting me.

JON: You were shooting film in that scene?

ROBERT: I believe that was the only scene where Haskell put real film in my camera. Then he told me what to shoot, where to shoot. We were standing right next to each other. I’m not sure if he used any of my footage though.

JON: Did you train as a cameraman before you took the part?

ROBERT: No. But I’d held that camera a lot by then. And I knew what these guys did. How they held it, how they looked for a shot.

WAITRESS: (refilling my iced tea) Robert, you want more coffee, honey?

ROBERT: I’m good for now, sweetheart. Thank you.

JON: You must have had press credentials when you shot the National Guard as well?

ROBERT: Those were pretty easy to get. It was just a training exercise.

JON: But again, you went in posing as real journalists?

ROBERT: Yeah, they thought we were journalists. We presented ourselves that way. I mean there might have been some people who thought, “Hey, what is this Channel 9?” It was a phony channel.

JON: So you’ve got a real camera, Bonerz has real sound equipment, and Haskell is shooting. Who else is there with you?

ROBERT: Haskell’s camera assistant. Maybe one or two others. But all of us look like we’re an actual news crew.

JON: Did anyone get wise to what you guys were really doing?

ROBERT: Well, Haskell wasn’t shooting me every minute. He was shooting off me, panning to the subject, panning from the subject back to me. He knew how to do it.

JON: You don’t appear in the most dangerous scenes, like the police action in the park. It looks like Wexler is about ten feet away from getting his head cracked open.

ROBERT: I wasn’t in any of the scenes where Verna Bloom is wearing that yellow dress. I wasn’t there that day, but there was all kinds of chaos. We were sitting in the hotel once, we’d been waiting for some time, then Haskell came running in and said, “You won’t believe what’s going on down on this street!” And we all up and hustled down there to see what we could make from it. It was a lot of that kind of thing.

JON: That was a great decision, by the way, putting Verna in that bright dress. No matter how deep in the background she is, you can always pick her out.

ROBERT: Exactly.

JON: How could she just keep going up to all those people? Wasn’t she terrified?

ROBERT: I don’t know how she got through that day. I do know one thing, though: every actor, when they’re in front of the camera, they feel invulnerable. You really do feel like you’re Superman.

JON: Did anyone in the cast or crew get hurt?

ROBERT: I don’t think so. Not to my knowledge. Now, what’s interesting is the moment when the police throw down that tear gas, and that crew member yells, “Look out, Haskell! It’s real!” That to me is really something, but I’ve also read articles where people claim that line was added in later.

JON: Oh, I don’t think so. I just watched it again last night. It sounds entirely too spontaneous to be a dub. You know, he’s using natural sound throughout the sequence; you hear people in those crowds yelling all kinds of things.

ROBERT: I don’t think it was made up either, I just know some people say that.

I still had the rented DVD, so I watched the scene again, this time with the commentary track… where Haskell Wexler admits the line was put in later. D’ohh!

JON: A lot of famous media names either covered the convention, or were protesting. Did you ever cross paths with Dan Rather, Mike Wallace, Hunter S. Thompson, Norman Mailer, Phil Ochs, or Allen Ginsberg?

ROBERT: All those guys were there? I didn’t see any of them. The one guy I remember being around was Studs Terkel. He helped us out with some things. He got a credit on it.

JON: When did you first see the completed picture?

ROBERT: It was out here, I think. It was a screening. It was…

JON: What did you think of it?

ROBERT: Honestly, I didn’t know what to think. It was a very different kind of movie. Certainly very different from the other two movies I’d done. I remember it opened around the same time as Easy Rider, and there were some similarities between them, I guess. They kind of played the same way. But Easy Rider was a huge success. This one really didn’t do that well.

JON: When did it hit you that Medium Cool was becoming something of a classic?

ROBERT: As the years went by. I’d hear people talk about it. And I’d read things about it, here and there, magazines, books. It really impressed certain people. I’ve even had a couple cameramen come up to me over the years—major guys—who told me that was the movie that inspired them to become cameramen! And, you know, there’s the whole historical aspect of it. It really is like a time capsule, or a newsreel, of those times. I’m still not a person with strong political views, but I’m proud of it. It’s a wonderful picture.